NEWS Ryo Morimoto unpacks many moving boxes from Germany and sets up snail aquariums while establishing his new laboratory at Umeå University. “I believe I might be the first researcher to introduce snails as an experimental system in Umeå,” he says enthusiastic with a smile.

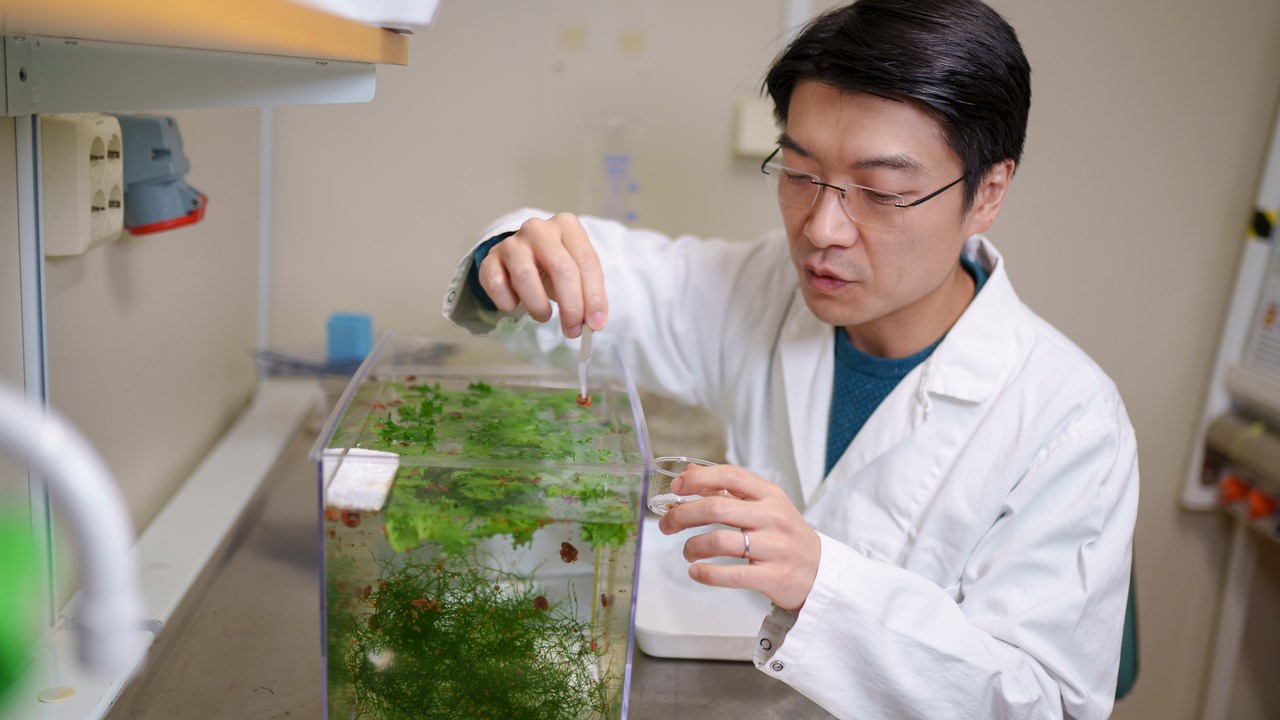

Ryo Morimoto collects snails from the aquarium. His passion lies in basic science, with a focus on unravelling the pathophysiology of various human diseases, which may also have implications for clinical medicine.

ImageMattias Petterssonhaving my own lab for the first time opens exciting opportunities

Snails offer a simplified perspective on the complexities of human immunity, making them a valuable model for understanding fundamental immune mechanisms. This approach allows him to carve out his own distinct research niche to pursue his scientific interest as a principle investigator.

“There is fascinating evolutionary science to explore here in Umeå, and having my own lab for the first time opens exciting opportunities,” says Ryo Morimoto, research fellow in the Department of Molecular Biology and Group Leader at the Laboratory for Molecular Infection Medicine Sweden, MIMS, at Umeå University.

Ryo Morimoto investigates the evolution of the human adaptive immune system using a unique lens – non-conventional model organisms. Adaptive immunity is a cornerstone of vertebrate self-defence against pathogens. It emerged relatively recently on the evolutionary timescale, around 500 million years ago, coinciding with the emergence of vertebrates.

The human immune system has evolved to become highly sophisticated, yet its foundation is built on ancient features. Over time, it has developed intricate fine-tuning mechanisms to minimize the risks associated with adaptive immunity while maximizing its effectiveness. However, this refinement often obscures the ancient core features of adaptive immunity.

Ryo Morimoto’s current project focuses on a family of enzymes that serve as critical evolutionary building blocks shaping adaptive immunity.

“We employ a multidisciplinary approach that combines in vitro biochemistry of these enzymes, single-cell omics, advanced imaging, computational genomics, and in vivo techniques. Our goal is to uncover the fine-tuned mechanisms regulating physiological genome editing within the immune system,” says Ryo Morimoto.

Ryo Morimoto is establishing his new lab at Umeå University and is currently looking for a postdoc and a PHD student.

ImageMattias PetterssonRyo Morimoto was born and raised in Japan. His passion for molecular biology was sparked during his middle school years.

“I still remember being 14 or 15 years old, sitting in a science class instantly captivated when our teacher introduced the biochemistry and molecular biology behind cellular respiration,” he recalls.

Over time, his curiosity expanded to encompass a broad range of life sciences, eventually leading him to enrol in medical school at the University of Tokyo. The university’s strong research focus resonated deeply with Ryo. Early in his studies, he approached professor Takao Shimizu to request a spot in the lab so he could conduct experiments.

“That is how I spent my mornings, evenings, and weekends – immersed in the lab outside of medical classes! The only time I was not in the lab was when I was hiking in the Japanese mountains. Research became my hobby,” he says with a smile.

After graduating from medical school in 2011, Ryo completed two years of clinical residency in teaching hospitals, gaining experience across various fields of medicine. He found clinical work deeply rewarding and enjoyed being a physician. However, the cases that stayed with him most were those where modern medicine offered little help – patients for whom no specific treatment existed or where even a correct diagnosis was elusive.

“It was both serious and frustrating for me. I wanted to do something for these people, to contribute long term by understanding the pathophysiology of diseases through basic science,” Ryo reflects.

Ryo realized that while he could make a difference as a medical doctor, his true passion lay in exploring the molecular and biochemical mechanisms underlying diseases. This led him to pursue a PhD in biochemistry at the University of Tokyo. His doctoral research delved into lipidomics, with a focus on phospholipid metabolism and inflammatory lipid mediators.

“I was curious about understanding the regulatory mechanisms that drive diversity in biological processes and towards the end of my PhD, I began exploring ways to apply this interest to more in vivo model systems,” Ryo says.

At a multidisciplinary conference in Berlin, he attended a talk by professor Thomas Boehm, who would later become his postdoctoral supervisor. The presentation described the alternative adaptive immunity found in jawless vertebrates.

“It was love at first sight. I was completely captivated by the idea.”

Supported by a prestigious JSPS overseas fellowship, he could move to Freiburg in Germany, to join the Max Planck Institute of Immunobiology and Epigenetics as a postdoctoral fellow,

“Not only did I enter a new scientific field, but it was also my first time living outside of Tokyo!” he says.

Over the following seven years, Ryo focused on studying the evolutionary trajectory of vertebrate adaptive immunity. His research centred on the diversification of anticipatory antigen receptors in jawless vertebrates, particularly the European brook lamprey. It was essential to compare animal models at different stages of evolution. In addition to lamprey, he also worked with other model organisms, such as sharks, zebrafish, and mice.

The studies provided critical insights into the implications of alternative adaptive immunity for the human immune system. His most important discovery was providing molecular evidence that an enzyme called cytidine deaminase is responsible for the somatic assembly of lamprey’s alternative antigen receptors in their adaptive immunity.

“Interestingly, the enzyme that belongs to the same family plays a central role in humans for antibody class switching and somatic hypermutation, highlighting the deeply rooted evolutionary function of this enzyme family in adaptive immunity,” Ryo says.

One of the unusal model organisms is the Water snail, Biomphalaria glabratais. Its native distribution includes the Caribbean. One snail can lay 14,000 eggs during its whole life span, which is 2 years. Every month a new generation is born and it grows to the size of 1-2 centimeters.

ImageMattias PetterssonIn 2022, Ryo advanced to project leader within the same research group. This shift made him more conscious of his responsibilities as a team leader, transitioning from a focus on bench work to guiding and supporting others.

Ryo sought for the next step to establish himself as an independent researcher. While searching for opportunities, he came across an interesting advertisement online for a position at the Laboratory for Molecular Infection Medicine Sweden, MIMS, at Umeå University in Northern Sweden.

Fast forward to today; Ryo has been working in Umeå for more than half a year. He thinks that the quiet environment here allows him to focus well on his research and plan the next steps to let his team grow.

He is also impressed by the friendly and inclusive culture in Sweden and does not miss the constant buzz and stimulation of a big city like Tokyo.

“I adapted to life in Europe much better than I initially expected. Before leaving Japan, I thought I might return after just a few months or a couple of years. But I find myself still here, well settled in the society!"

Ryo Morimoto is taking care of snail's food. Adults in captivity can be fed with lettuce. The young ones are given dried salad in powder form.

ImageMattias Pettersson